|

ADAMS WATERWAY By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

|

ADAMS WATERWAY By Jerry Wilkinson |

|

|

Throughout Monroe County, boaters who wish to travel from the Atlantic

Ocean to Florida Bay usually do so by passing through one of the many

natural

passageways between the hundreds of islands which make up Monroe

County.

Monroe County has been labeled a "County of Islands."

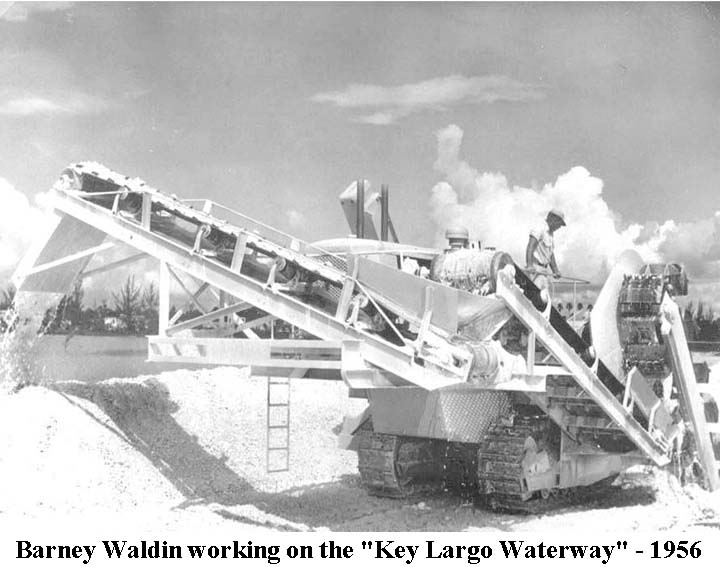

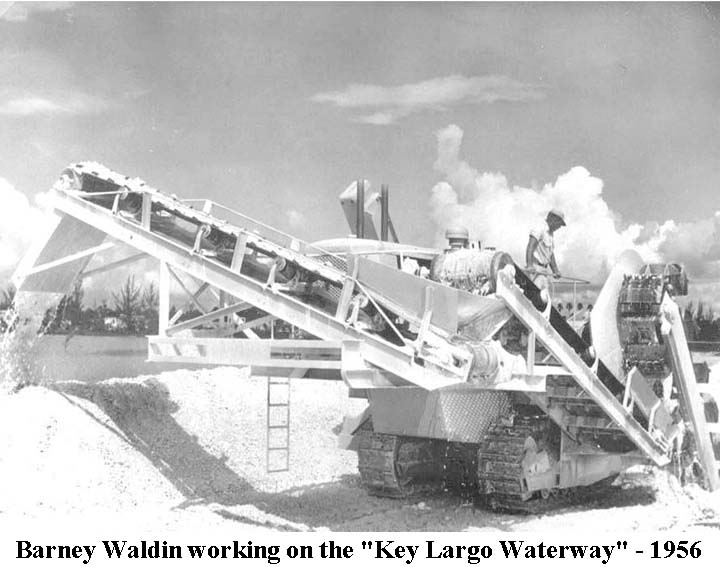

There is, however, one waterway that is an exception. It lies about midway of Key Largo at mile marker 103.6. Speeding autos on highway U.S. 1 pass over the bridge and their passengers barely notice it. However, for those who pass through it in a small boat, it is a different feeling. The vertical walls rise some 15 feet straight up. If the ocean tide is changing, the water will rush past them almost like river rapids. Boaters are certain this passageway has been intentionally cut through the island, and cut it actually was. For many of us in our hurry-up way of life, it is simply a short cut from ocean to bay, or vice-versa. Without it, one would have to travel southwest to Tavernier Creek or northeast to Angelfish Creek to cross over. This man-made waterway basically reduces the distance by one-half. Many local boaters refer to it as "the Cut." Even on land, when referring to a landmark or a business in that part of Key Largo, they will say, "Go one mile north of the Cut on the bay side...", or "Go just on the other side of the Cut and turn right...," etc. Some time in the 1920s, after the opening of the Panama Canal in 1915, a miniature canal across Key Largo was envisioned. For some boaters, going around the long, narrow island seemed as long as going around the tip of South America did for larger ships. It was not until the early 1950s that Marvin Dow Adams took the challenge seriously. Marvin Adams came to Miami in 1925 and became a partner in an insurance business as well as real estate. From a newspaper article in January 8, 1926, he was the sales manager for F. E. Sweeting who developed the Anglers Park Subdivision. In the early 50s, he purchased 50 acres of land that just happened to contain the narrowest stretch of land across Key Largo and about in its middle also part of Anglers Park. Its width was about a half-mile from Blackwater Sound to Largo Sound. It also crossed the high coral ridge that runs the length of the island. The land, about 15 feet above sea level, consisted of Key Largo Limestone. Marvin owned the land and the dream was in his mind. It was not the Panama Canal, but a major undertaking for a Miami insurance man, besides it would enhance the remaining part of his property. Marvin Adams had some practical knowledge of a project of this type and magnitude. He had served as chairman of the Florida Turnpike Authority, and knew something of government proceedings. He also knew that a study of necessity, feasibility and costs must precede the start of work. His cost estimates came back as $7,500 for engineering and $690,000 for digging, excluding the highway crossing. This seemed a bit expensive for Adams. Local businessmen Joe Lance and then President of the Upper Keys Chamber of Commerce, Van Sweringen, introduced Marvin to Mathew Bernard Waldin, owner of M. B. Waldin, Inc. "Barney" Waldin agreed to do the excavation at no cost providing he could have the loose material. "Barney" Waldin's father and grandfather had come from Iowa to the Keys to work for Henry Flagler's F.E.C. Railway. Both were aboard quarterboat Number Four when the 1906 hurricane struck. It washed the quarterboat from Long Key out through Hawk Channel and into the open sea with 161 men aboard. His father was picked up by a steamer and taken to Key West; his grandfather was rescued by another steamer and was taken to Savannah. While in Key West his father married and then moved to Homestead. Barney was born in Homestead in 1916 and married Marjorie Melhado in Key West. They settled on Plantation Key. With financial aid from the late Arthur Vining Davis, Barney invented, built and patented a machine that would cut deep trenches in coral rock. The machine consisted of two D-8 Caterpillar diesels mounted one on top of the other at right angles. The lower Caterpillar would propel the machine forward while the upper Caterpillar turned a rotating track with tough steel cutting blades acting as a saw. A conveyer belt carried away the loose material. See top photo. Barney's machine would cut a trench 18 feet deep and 34 inches wide and was the first ever to cut from the side, as opposed to the middle. Even in 1956 there were a few permits to work out. Not much clearing was required, as there was already an existing road in the path for the cut. Still the Corps of Engineers had to evaluate the land ecology and water disturbance elements at both ends. The U.S. Coast Guard quickly approved of the concept. They thought it would enhance their operations, and in addition, enable small craft to seek hurricane protection from ocean to bay much faster. With his turnpike experience, Adams had little trouble with the Department of Transportation, and telephone/electric utility coordination. The major stumbling block was the Seventh Naval District in Key West that was responsible for the relatively new fresh water pipe line. Cutting off traffic to install a bridge was one thing, but cutting off all the water to Key West and re-piping the pipe line was another. However, permission was finally granted and the problems would be worked out when the time came, probably on the assumption that the project would never happen. All systems appeared ready for The Key Largo Waterway, as it was known then. Marvin Adams hired Sheldon Stewart as chief engineer and Waldin starting digging at the Blackwater Sound end. He began just far enough back so that the water would not flood the channel. His plan was to dig two parallel trenches 100 feet apart and dynamite the center part. Holes were drilled 32 feet deep to set dynamite charges to loosen the coral. His drag line would then load the loose fill into trucks to be transported to local fill sites. Only the side walls were cut with the trenching machine. The depth below the water averages about 25 feet. Coral rock fill was selling then for about $1 a cubic yard. An immense amount of fill was removed and used throughout Key Largo. Even a small island was filled in the northwest corner of Largo Sound, and connected by a road and bridge (Island Drive). A year-and-a-half was needed to complete the half-mile cut. In 1958, the canal stood with its two ends plugged and a full section intact where the highway and utilities passed over. Barney had completed his part of the contract. Alonzo Cothron was contracted to finish the project. Like Barney, Alonzo's father came to work for Henry Flagler. In 1909, Reynolds Cothron worked on the Niles Channel Bridge, which was severely damaged by the 1909 hurricane. The 1910 census shows Reynolds as a railroad superintendent at Quarry on Windley Key, with his wife Mary and eight children. The 1920 census shows the Cothron family farming on Upper Matecumbe. Alonzo was then 16. At the time of the 1935 hurricane, Alonzo was working with H. S. McKenzie of Tavernier, building the two-story theater. He soon became the largest contractor in the Middle and Upper Keys.

To complete "The Cut" Alonzo built a temporary bridge on the bayside

and

excavated a bridge support level to 12 feet below water level. This

would

facilitate easy installation of the supporting columns for the new U.S.

1 highway bridge and associated utilities. Twelve years later, a second bridge was added when U.S. 1 was four-laned; however, one lane was a little lower on one side than the other. FDOT corrected this problem and added foot-traffic walkways in 1992-1993. In a 1976 dedication ceremony, the Key Largo Waterway name was changed and John Pennekamp wrote in the Miami Herald: "After the channel had been cut through Key Largo some years ago, Marvin D. Adams commented, 'Fortunately for me I have, more through luck than plan, changed the face of the earth in a way that is great satisfaction to me. That I will be remembered for this, I doubt.'"

He was wrong. The Monroe County Commission renamed the cut to the

"Marvin

D. Adams Waterway," and it continues to serve the Upper Keys community.

It could be the second most significant non-government private project,

the railroad being the first in our Upper Keys history.

-----End----- Return to General Keys History |